PT | EN

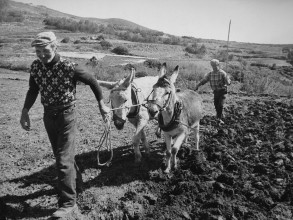

For centuries, agriculture was the main activity for people living in the municipality, although there seems to have been some delay in the region's adoption of new techniques and a tendency for excessive re-parcelling of the land.

Of a diverse geological nature, the land's harvests were considerable, as is proven by the fact that they produce reasonably despite being poorly worked with a rudimentary plough and without any manure albeit as soon as the year improves, that is, when the weather is not too dry'.

Agricultural work was therefore low-yielding and technologically deficient with production not even meeting domestic consumption needs. In reality, not even wheat farming (the most popular in the municipality) seemed to satisfy local demand.

The same happened with barley to a lesser degree, which was grown on inferior quality land for animal feed. Corn was also considered secondary, like other traditional crops such as oats and rye.

Saloios and their love of the earth

Agricultural activity is closely associated with saloio country folk who had been rooted to their land for generations and found themselves on the edge of Lisbon when it was conquered by King Afonso Henriques, after which they went on to develop their own culture which is reflected in their customs, beliefs, language and clothing.

Thus, they were heirs to the Arab tradition of tilling the land to grow cereals such as maize, wheat and barley, as well as vines, olive groves, fruit trees and vegetables.

These 'bread' lands normally stretched across the most elevated parts of the municipality where owners of small plots decided to join forces in order to increase their production and profits.

Vineyards were cultivated on the slopes and vegetable gardens were planted next to streams in places the Arabs called almuinhas, which are still evoked by the toponym Almuinhas Velhas in Malveira da Serra today.

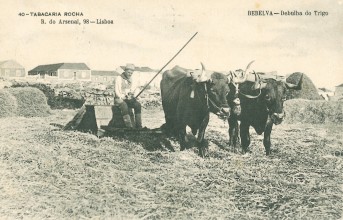

The production of cereals (wheat in particular) involved an extensive work cycle that began with 'ridging', a process that consisted of opening the furrow with a plough to mark out the land, followed by 'harrowing' to straighten the land with the harrow and finally the seed-sowing season would begin around December time. Once this task was over, it had to be 'furrowed' using a hoe to cover the seed.

This was followed by thinning to remove any weeds and facilitate the cereal's growth.

Harvesting took place from June to the beginning of July, followed by threshing which, until the introduction of mechanisation, was carried out on the threshing floor.

'You have to separate the wheat from the chaff'

The chaff is a harmful plant that often appears in fields of corn, affecting its growth. This rural expression was soon fitted to other situations, meaning that it is necessary to separate the good from the bad!

When the threshing was finished, the grain had to be spread across the threshing floor and the straw and speck were separated. Using traditional, elementary methods, the straw and grain were thrown into the air (preferably on windy days) and then bagged.

'In Gonçalo's house, it's the hen that rules rather than the rooster'

Saloio womenfolk combined their household chores with the farm work, such as cooking meals (which included bread-making), as well as gardening, collecting water and firewood and raising the children. They also sold agricultural products and tended to the animals.