PT | EN

With the invention of the steam engine in the middle of the 19th century, the agricultural industry transformed itself by easing some of the most arduous tasks, such as ploughing and threshing.

However, the municipality of Cascais would only witness this kind of evolution from the second quarter of the 20th century onwards, which changed the social nature of agriculture with the replacement of rhythms and even sounds, when the noises of straining engines imposed themselves on the voices of the workers.

The fields, therefore, no longer required so many people and farmers gave way to the specialised machinery being used for tilling the land, harvesting and even processing the agricultural products.

Cascais Stone

Due to the rocky substrate mostly made of hard and compact limestone, the job of extracting and working the stone has greatly involved the people of Cascais over generations due to the variety of the region's marbles, ashlars and decorative stones.

In 1873, Pedro Barruncho noted that 26 quarries were being mined, which over five years had produced some 7,324 truckloads.

Amongst the most famous stones, the stacked marble from Cascais stood out for its honey colour and many shell fragments, along with busano marble, the sturdy bastardo marble greyish with purple and white spots and Cascais azulino, a blue-grey limestone with light brown spots and a scattering of black dots.

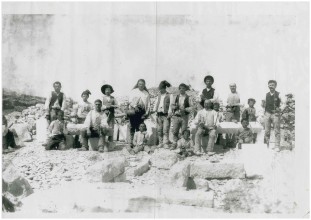

Quarries

The oldest-known quarry in the municipality dates back to the Late Neolithic period and was discovered during archaeological excavations at the Branqueiras site in Alvide.

Dating from Roman times, a quarry was also identified next to the Miroiço Roman Villa necropolis in Manique from where limestone pillars covering the graves were removed.

By the end of the 16th century, the quality and beauty of Torre da Aguilha's red marble was already being appreciated, because many loads had left the region's quarries to help with the reconstruction of the city of Lisbon after the 1755 earthquake. Thus, in 1763, quarrymen represented approximately 34% of the working population in S. Domingos de Rana Parish Council.

In 1900 it was reported that 'the men employed in the quarries are called 'quarrymen' and have their own language, so to speak. They say that the deepest quarries are named royals and are therefore more labour-intensive; they call the rock banks tonas and refer to the eruptive veins that cross the quarries as royal cables'.

Stonemasons

The work of the stonemason, whom José Luís Tomé Sabido described as 'the person who works stone in all its aspects', was multifaceted, executing simple curbs for roads or pieces of a surprisingly artistic nature.

For that reason, there are many examples of its activity throughout the municipality, namely on churches, houses, fountains, crosses, statues and tombs.

The more skilful stonemasons were entrusted with the most delicate work, such as sills, thresholds, columns, bases, shafts, capitals, balusters and cornices. The others (including apprentices) took care of the plinths, jambs, lintels and sinks.

At this time, 'the execution of stonework was done manually with the help of a mallet, chisels (oothed or smooth, rods, picks, hammers toothed or smooth, lump and bush hammers', with the quarries of Coveiras located on both sides of the pathway between Tires and S. Domingos de Rana being one of the main sources of the region's stone.

Nevertheless, this profession began to disappear thanks to mechanisation, the gradual depletion of the quarries and the growth of localities in the municipality.